Black Literary History

The history of Black American literature is inextricably bound with the narratives of its writers: first the Africans forcibly transported to the American colonies, some of whom gained a measure of freedom in the late 18th century; the native born who pursued and advocated for freedom for themselves and their brethren in the 19th; the tumultuous writers of progress and protest in the 20th; and the dreamers and the galvanized of the 21st. What Brooks writes in her poem about the civil rights activist and concert artist Paul Robeson —“we are each other’s harvest /… we are each other’s / magnitude and bond”—functions as an ethos to this great conversation across time and literature. What does it really mean to be a Black American writer?

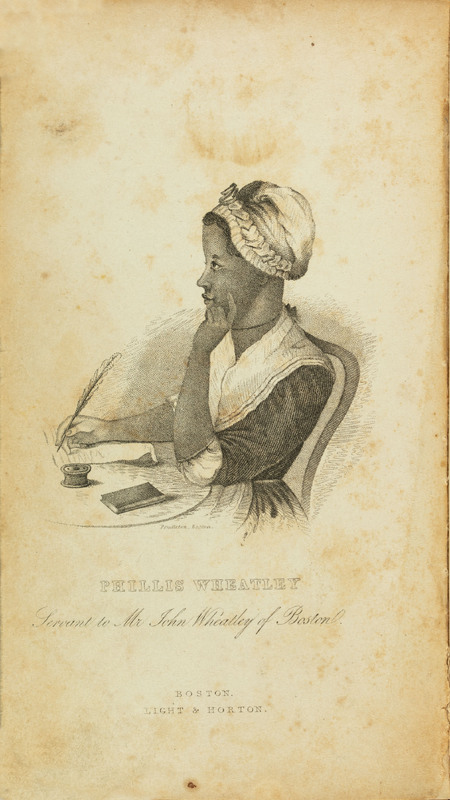

Conventional histories of Black American writing begin with Phillis Wheatley (1754–1784), a young woman kidnapped from Africa and educated by her white enslavers. Caught in a complex situation where her ability to truly speak her thoughts was inherently undermined, she nonetheless used her fame as a poet to lobby for abolition and eventually attained her freedom.

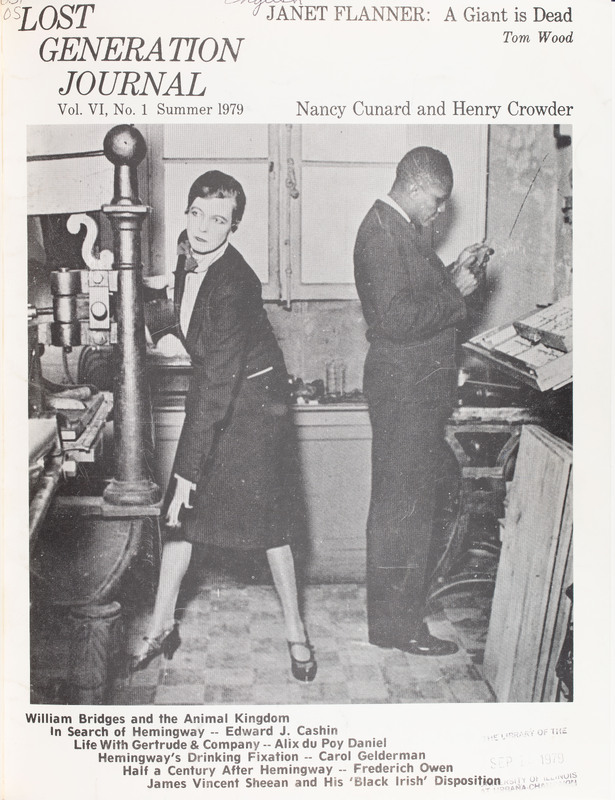

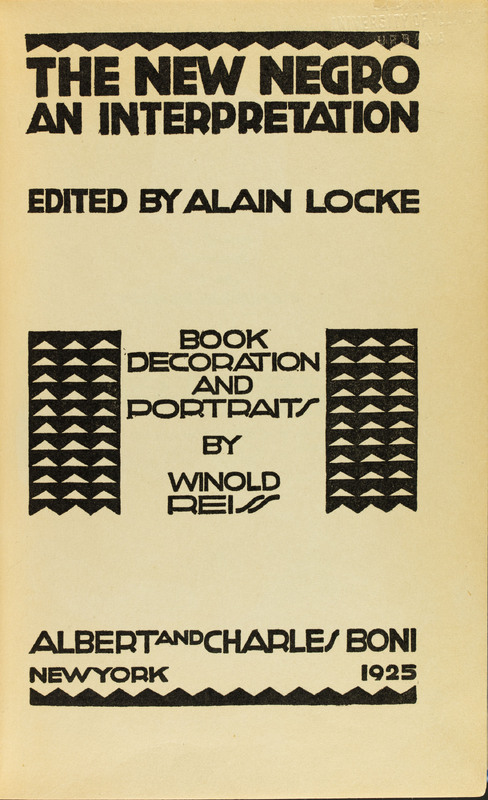

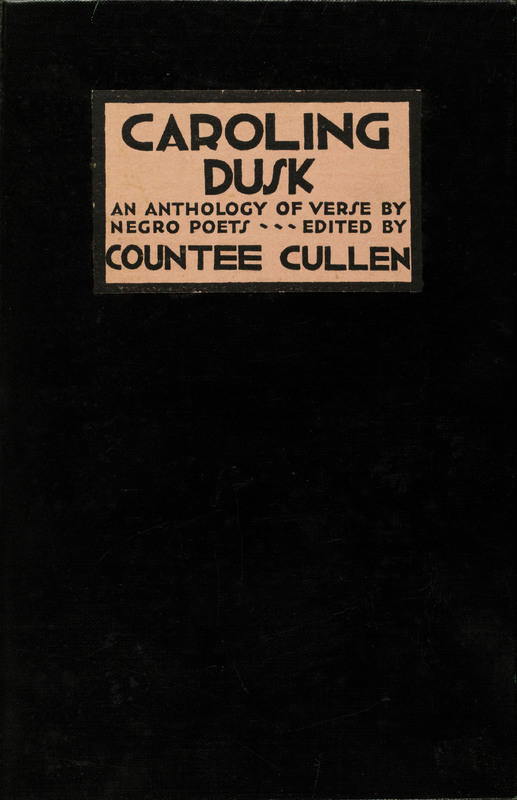

Black activists of the 20th century wrote from a different position, but still one in which they were advocating for political equality to white audiences. Countee Cullen (1903–1946) and Alain Locke (1885 –1954) both collected Black writing, Cullen as a historical retrospective and Locke to highlight the generation of the Harlem Renaissance. The volumes speak to one another as a dialogue. The anthologies of Nancy Cunard (1896–1965) and Sterling A. Brown (1901–1989), Arthur P. Davis (1904–1996), and Ulysses Lee (1913–1969) similarly speak to political and artistic activism.