This exhibition of early editions of and texts referring to Plato’s Timaeus, including three incunabula and one manuscript, was created to accompany a four-day conference; "Life, the Universe, Everything —and More: Plato’s Timaeus Today," held at the University of Illinois, September 13th to 16th, 2007. The conference spanned the time from Presocratic influences on the Timaeus up to examples of post-modern architecture that employ the notion of chôra (space/matter) and the image of Atlantis from the Timaeus. A, if not the, climax of the reception of Plato’s Timaeus in the Renaissance is the focus of the exhibition itself. The translations that helped Plato’s Timaeus survive as the only Platonic text known to the Latin West during most of the Middle Ages are shown, as well as works exemplifying important stages of the reception of the Timaeus. Accordingly, the items in the exhibition are divided into two parts; the first part comprising different translations of and commentaries on the Timaeus; the second featuring works employing and critiquing central ideas of the Timaeus more broadly.

The books on display date from the 15th century to the early 17th century — a time marked by manifold political, scientific and technological changes, changes which are reflected in the various editions on display. The political transformations include the increasing military pressure of the Ottomans against Constantinople, leading eventually to its fall in the 15th century. This pressure forced many attempts at a closer political cooperation between the Latin West and the Byzantine Empire, which eventually proved to be ill-fated. However, these efforts did result in a closer intellectual exchange, which included the diffusion of the Greek text of the Timaeus into the Latin West (one of the first Greek editions is in the exhibition). This exchange also motivated Cosimo de Medici to found the Platonic Academy in Florence following the example of Plato’s Academy. One of the Academy’s first heads, the Plato scholar Marsilio Ficino, produced the first complete translation of Plato’s works. In the exhibition there are several editions of this translation and commentary on the Timaeus.

The new technologies of the Renaissance appear, not least of all, in the fact that most of the exhibits shown were printed – the process of printing from moveable type had just been invented in the mid 15th century and helped Plato’s works, which had been neglected in the late Middle Ages in the West, to spread rapidly after their re-discovery in the Renaissance. Among the printers, publishers and typographers of the late 15th and early 16th century, Aldus Manutius was one of the most influential. From Venice, a city already famous for printing, Manutius produced many of the first editions of the Greek and Latin classics, is said to have invented italics and the standard font for Greek. The latter can be seen in his editio princeps of the Aristotelian corpus, a volume of which is on display. Another famous printer and publisher also represented in the exhibition was Henricus Stephanus, whose 1578 edition of Plato on display here set the standard pagination for Plato’s works.

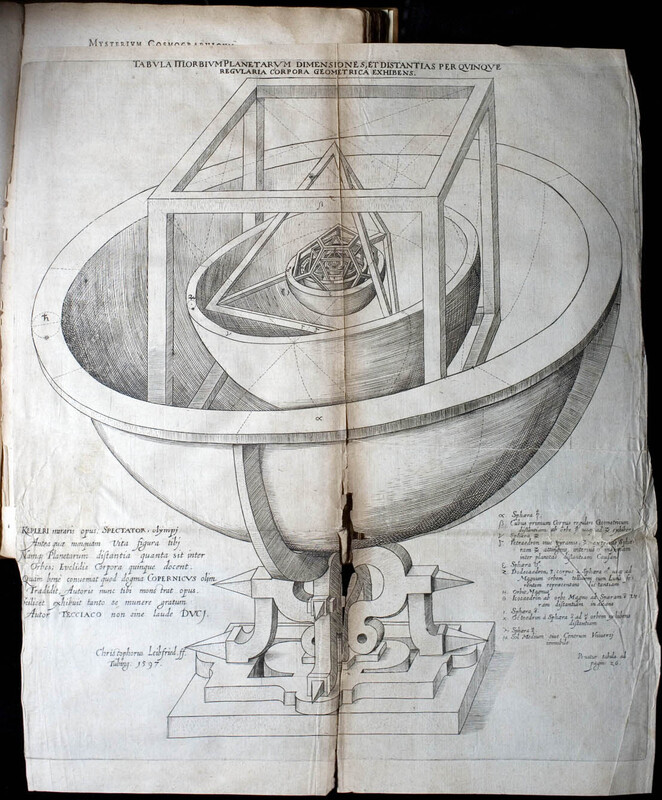

Finally, the Renaissance enjoyed a newly awakened interest in the sciences, especially in astronomy, which we can see, e.g., in the editions of Kepler’s works in the exhibition. For him the mathematics and physics in the Timaeus were particularly important, and the improvements in the knowledge of Southern constellations that this new interest spawned are reflected in our display of Johannes Bayer’s star map.

Release the Stars: Plato's Timaeus in the Renaissance: was originally a physical exhibit on display at the Rare Book & Manuscript Library from September 14th to November 9th 2007.

Acknowledgements

Curated by Barbara Sattler, Bruce Swann, and Angela Zielinski-Kinney. Exhibit coordinated by Dennis Sears. For help with the research with all the introductory texts I am very grateful to Stephen Menn (McGill). For help with mounting the exhibit and the Web site, special thanks go to: Rebecca Bott, Kyle Broom, Chris Cook, Rob Hildreth, Valerie Hotchkiss, University of Illinois Mathematics Library, Sherataun Nuss, Misty Oakley, Noah Pollaczek, and Marten Stromberg.