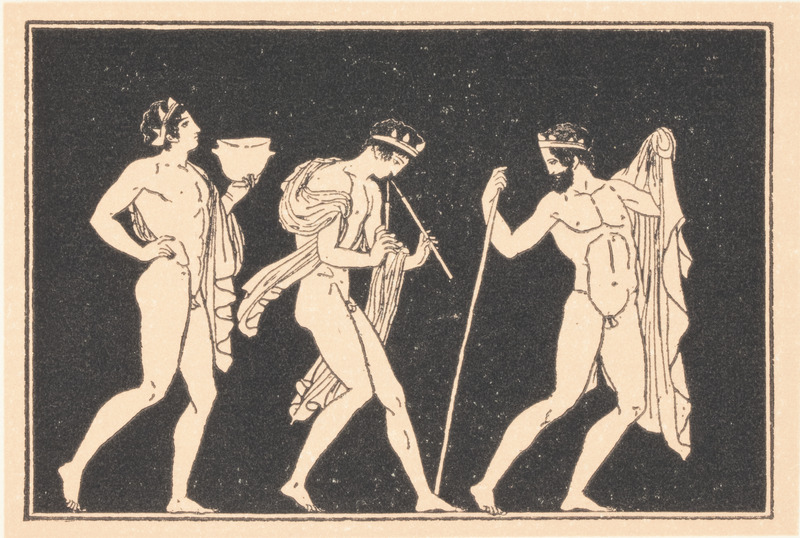

Ἔρος δηὖτέ μ’ ὀ λυσιμέλης δόνει,

γλυκύπικρον ἀμάχανον ὄρπετον

Eros once again limb-loosener whirls me

sweetbitter, impossible to fight off,

creature stealing up

Sappho, Fragment 130, line

trans. Anne Carson

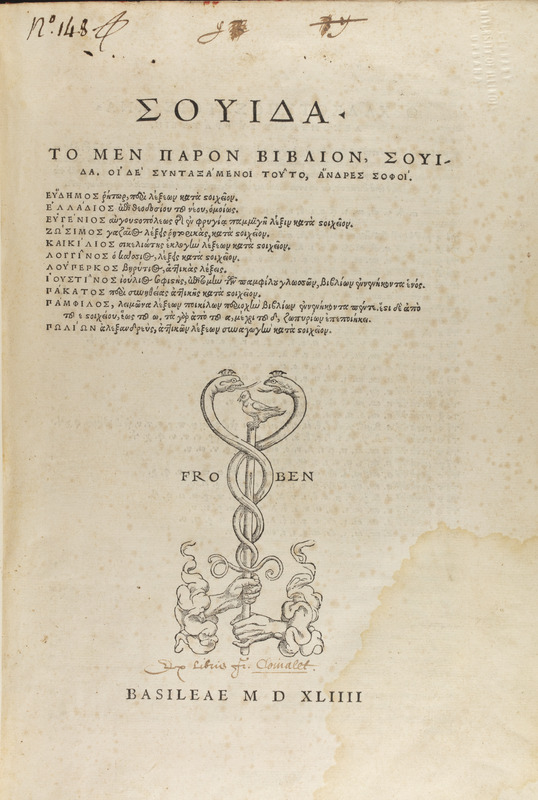

As with many ancient writers, the story of Sappho’s life comes to us in bits and pieces. The Suda, a 10th century Byzantine encyclopedia attributed to a writer named Souidas, records two Sapphos: one, the poet, and the other a woman who fell in love with a ferryman named Phaon and eventually committed suicide by jumping from the Leucadian cliffs. The poet’s entry regurgitates the handful of details we have, such as place of birth (Mytilene, on Lesbos), a possible husband (the name Kerkylas of Andros may be a joke, as it translates roughly to “Richard of Dick Island”) and child, and the fame and renown of her lyrics. In the late medieval and early modern periods, scholars continued to compile sources and link those narratives to more recent histories. The 1521 collection De memorabilibus et claris mulieribus, or “On Memorable and Famous Women” combines several texts, including biographies of saints with Plutarch’s “On Virtuous Women” which discusses Sappho specifically as a woman poet. By the eighteenth century, an account in Pierre Bayle’s Historical and Critical Dictionary declared that Sappho was “one of the most renowned Women of all Antiquity for her Verses and her Amours” for “you must know that her Amorous Passion extended even to the Persons of her own Sex, and this is that for which she was most cried down.” Over the centuries there have been various theories and ways to describe Sappho’s community of women, her friends and lovers. Maximus of Tyre (2nd century CE) considered Sappho’s circle of women analogous to Socrates’s group of male friends and students, queerness and all. The names of Socrates’s friends come from Plato’s account in The Symposium, a series of dialogues by Greek philosophers discussing the nature of love and sex.

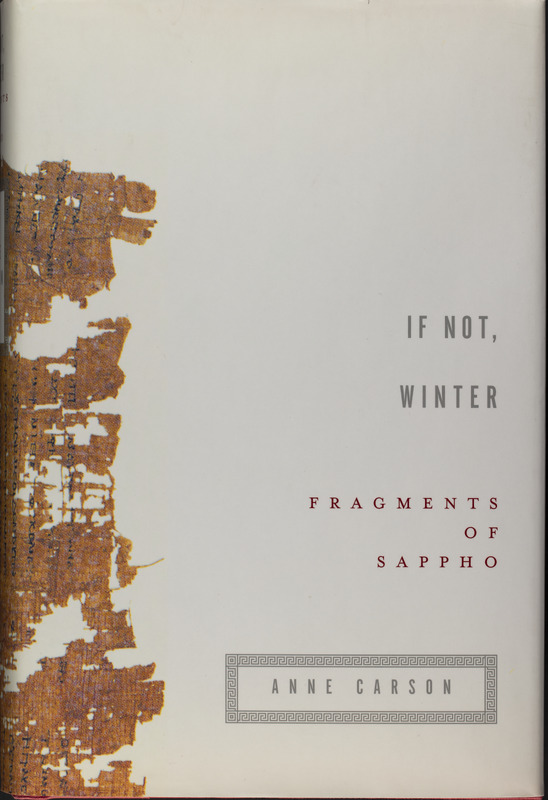

In our time, we have come to view Sappho as an icon of intellectual and romantic freedom. As one of the earliest surviving women poets, we continue to trace her influence and her popularity, following her work in new translations over time. Perhaps the most significant in the twenty-first century so far is Anne Carson’s 2002 English translation If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho. In the act of reading, Sappho is not the only unrequited lover: So is the reader.