αἰ δὲ μή, ἀλλά σ᾽ ἔγω θέλω

ὄμναισαι[. . .(.)] [. .(.)]. .αι

καὶ κάλ᾽ ἐπάσχομεν

But even if you won’t remember me, I want to remind you [...]

of the pleasure, the many tender things we experienced.

Sappho, Fragment 92

trans. by Panagiotis Sotiroudis and Eleonora Mylli, adapted by Malina Infante

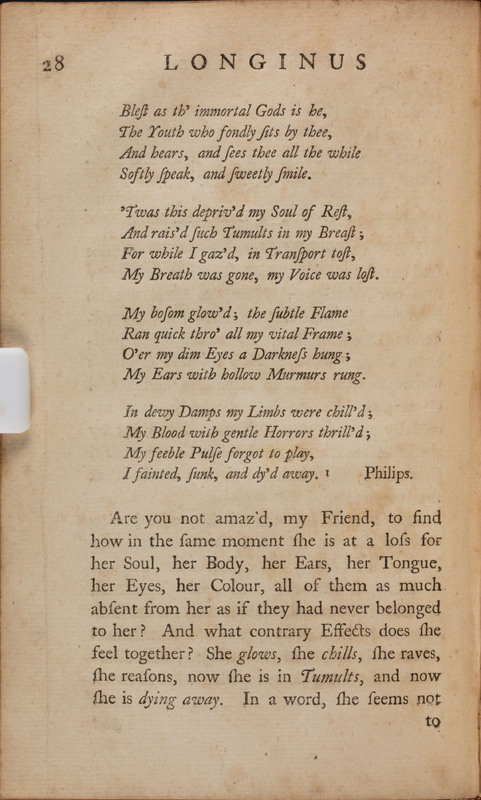

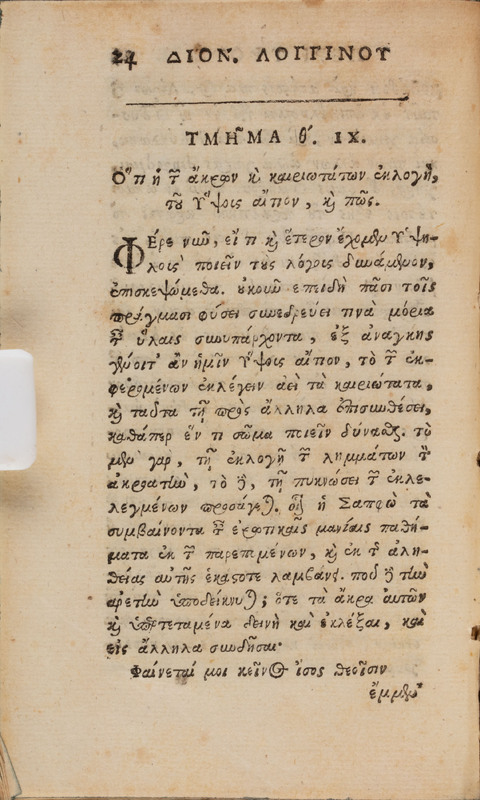

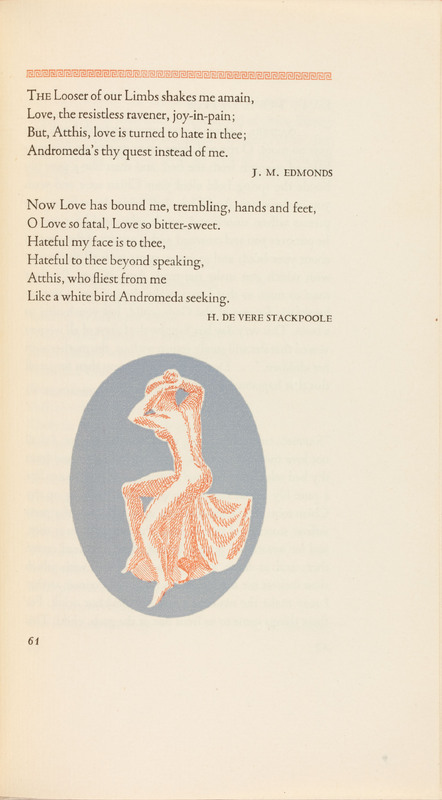

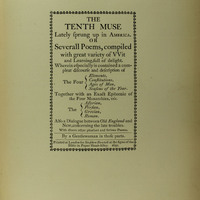

Ancient sources state that Sappho’s lyrics encompassed nine volumes, of which some 650 lines and precisely one complete poem survives. Composed around the time early writing systems were being developed, it is likely her lyrics were not written down for more than a century after her death. Surviving material comes primarily from quotations in classical works by other authors. For example, the poem known as Fragment 31 was excerpted in the work of Longinus (1st century CE) in his treatise on aesthetics On the Sublime. “Sappho… always chooses the emotions associated with love’s madness from the attendant circumstances and the real situation,” he wrote. Longinus’s text analyzed the works of several dozen authors from the ancient world; he commented on Homer, various other Greek authors, and, intriguingly for the time, on the Book of Genesis. Placing Sappho’s lyrics alongside epic verse and Hebrew poetry, Longinus invites the reader to consider what makes great works truly great. By the twentieth century, editions of Sappho took on a variety of forms, from the scholarly to the salacious. The Songs of Sappho in English Translation by Many Poets, published by Peter Pauper Press in 1942 as a finely printed “gift book” for the American market, presents various versions of each poem by well-known translators. In this format even the casual reader can admire how single word choices can alter the mood or meaning of each poem. In retrospect, this presentation is all the more interesting given that such works were being avidly collected in the United States and banned as amoral in Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. Songs appears as a quasi harbinger of the Cold War as it would soon take place in books.

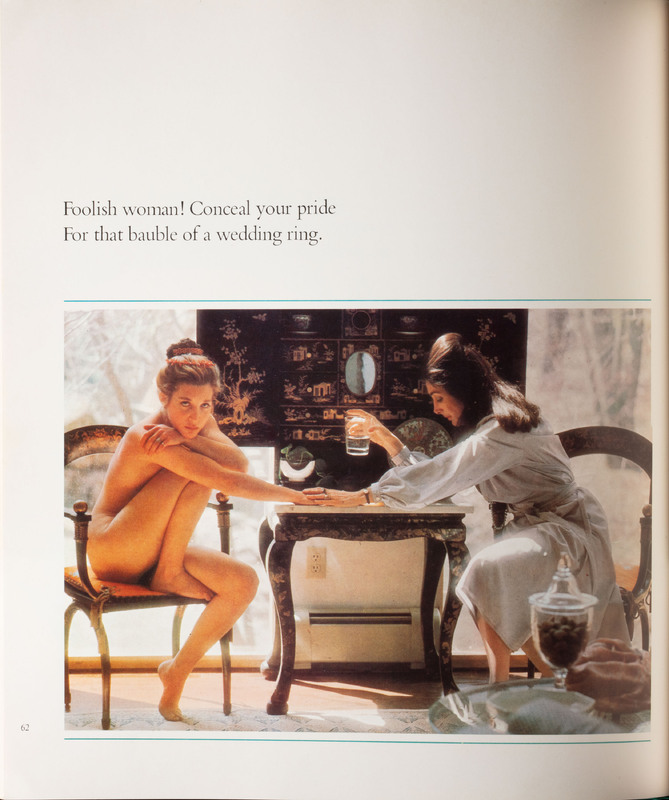

A few decades later, Sappho would reappear as a consciously counterculture figure. J. Frederick Smith’s The Art of Loving Women: The Poetry of Sappho (1975) combines photography and verses to create a curious coffee table collection for the Age of Aquarius set. The nude women shown throughout the book are what we might consider tasteful, conventionally attractive, mostly white, and artfully made up even in natural settings. Initially a magazine illustrator and pin-up artist, Smith moved on to photography in the 1950s; his claim to fame is being the cover photographer of the first Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue in 1964. The same qualities that suffuse similar works of the period by other artists are visible here: a slight cheesiness, an emphatic male gaze, and a peculiar sort of erotic innocence in the pre-internet world.